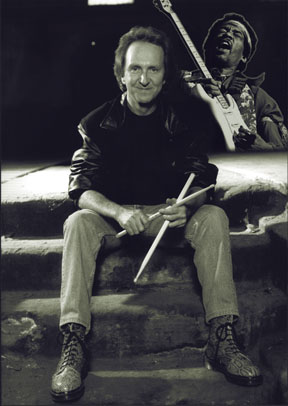

The Hendrix Experience

by Andy Doerschuk

Interview by Nicky Gebhart

There has been - and continues to be - no shortage of great rock drummers out there, many who have contributed to the collective vocabulary and influenced countless others who followed. Distinguished names come to mind, like Bonham, Starr, Watts, Moon, and Baker, who long ago earned lasting respect. But there's only one who, in the span of a few whirlwind years during the late '60s, rewrote the rules of rock drumming so completely that things could never be the same.

For that, you can thank Mitch Mitchell, the drummer with the Jimi Hendrix Experience, who could be loose and funky, or sharp and precise, or soft and spacey, a thunderous backbeat or a wisp of breath - all within one song. Before then, such depth was absent from rock drumming, and the impact was profound...

Go back and listen to Mitchell on Are You Experienced, the band's 1967 debut album. Whatever happens, Mitchell goes wherever the guitar goes, relying on instinct as much as technique. And the guitar went wherever Hendrix took it, which meant, of course, that it went to places that hadn't existed before then. Together they enlivened rock with a newfound level of improvisation, unorthodox riffing, tonal liberation, and sheer speed and power that stands unmatched to this day.

Yet, during the years since the guitarist's untimely death on September 18, 1970, the Hendrix legend ballooned to such mythical proportions that it all but obscured Mitchell's groundbreaking contribution to the band's sound. And that is nothing short of criminal, because those drummers who based their entire methodology on the unique combination of fire and grace that defined Mitchell's work with the Experience know that, for utter historical innovation, his drumming matched Hendrix's guitar wizardry note-for-note.

To hear Mitchell tell it, his introduction to Hendrix was hardly the weighty stuff of drumming lore. It could've just as easily never happened. In the mid-'60s, while still in his teens, Mitchell established himself in London, where he worked as a sideman and session drummer for various bands, including Screaming Lord Sutch and Johnny Kidd and the Pirates.

"It was an early equivalent, I suppose, of the brat pack," he says. "There were a few young players in the studios at that time in London: Johnny Baldwin [John Paul Jones], Jimmy Page. There was this one street, Denmark Street, which was like London's Tin Pan Alley. All the music publishers were there, and consequently, most of them had their little recording studios in the basement, and you'd go and do demo tapes for whoever it was.

"A lot of times, you didn't know who the heck it was for, because we were recording backing tracks. It could be Tom Jones, it could be Petula Clark. I did some things for Ready, Steady, Go, which was a TV program. Basically, you would take on anything that moved, and if you were lucky enough, you progressed from doing Denmark Street demos to the proper Musicians' Union sessions, which paid us a little bit more."

In 1966, Mitchell was working with Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, a well-known r&b act in Europe that had scored a respectable international hit the year before with "Yeh Yeh." Mitchell visited Fame's office every Monday to collect his weekly earnings, until one fateful payday when he was informed that the entire band was sacked. "My face sort of hit the floor, it was so unexpected," he recalls. "I literally walked down Charing Cross Road past all the music stores, back to Denmark Street - it was like going back to your roots, basically - and I went to a coffee bar just to think things over.

"Apart from being pretty devastated, my first thought was, 'I'm 19 years old. What am I going to do? What do I want to do?' I thought, the first thing, of trying to form some kind of band of my own. [Laughs] That lasted about five minutes. Actually, I did get a session that afternoon and that kind of brought a smile to my face. I thought, 'Well, okay. I have the choice of either going back to the studio or hopefully, if I'm lucky enough, I'll get gigs.' I did like the idea of working on the road with a band. It just seemed right."

Absolutely right, because Mitchell would soon receive a phone call from Chas Chandler, the former bassist with the Animals, who had since gone into band management and production. "I knew Chas vaguely from the Animals," Mitchell remembers, "and he said, 'Hey look, do you want to come and have a play with this guy I brought over [from America]?' I didn't realize it at the time, but of course, it was an audition.

"I went down to this little basement strip club in Soho and there was Jimi with a Fender Stratocaster upside-down with a kind of fake London Fog raincoat on, with his wild hair, and Noel Redding, who had been playing with Jimi I think for a couple of days, who I found out later was a guitarist, really, playing bass. I think there was a keyboard player, if memory serves me right, from Nero and the Gladiators. That was the idea first off, to maybe have a keyboard player.

"I just took down a tiny little Ludwig drum kit and said, 'What do you want?' basically. 'What are you looking for and what's it about?' I remember to this day, these tiny little amplifiers, and Hendrix was not happy with these little amplifiers so he was starting to kick them around. Like a lot of auditions, it really came down to the lowest common denominator. [We played] a bit of Chuck Berry, a bit of this, bit of that. I just threw in my Deutschmark, whatever you want to call it.

"He played a couple of things on the guitar that I found interesting - the style - and it kind of sparked me off. I used to get a lot of demos from, like, Curtis Mayfield, early Impressions things. And Hendrix was the first person I'd ever seen who could actually play that Curtis Mayfield style, which was unusual. So I named a Jerry Butler song, or an Impressions thing, and he knew it and could play it, and I thought, 'Oh, interesting.' I mean, I'd never been around that area of music before."

After jamming about 45 minutes, Mitchell packed up his gear and went home, feeling "intrigued." Two days later, he received another phone call from Chandler, who once again invited the drummer to jam with Hendrix, only this time, when he showed up, Mitchell found that there was no keyboard player - just the core power trio that would soon become internationally known as the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

At first, the three-piece lineup reminded Mitchell of Cream - a star-studded supergroup featuring Eric Clapton, Jack Bruce, and Ginger Baker - which had become the talk of the town around London. He remembers, "I came out with some facetious comment like, 'So, you want me to try to play like Ginger Baker or something?' Hendrix just goes, 'Oh, yeah, whatever you want, man.' But I did get the impression on that second time playing [together] that something was released. It was like a feeling of freedom. I don't know if it's a spiritual awakening. It was just a situation where I'd gone, 'Hey, you've never worked in a three-piece band in your life, ever, and there is something with this player that is very, very special.'"

Mitchell wasn't alone. There were plenty of other drummers around London who wanted the gig. "What did surprise me, very much, is that it appears that a lot of people had been going for auditions and had been playing with Jimi for about two weeks prior to me hearing about this," he says. "London's not that large a place, and in those days, there weren't that many drummers about. A lot of my peers, colleagues - call them what you will - they'd gone for the job. Aynsley Dunbar and Mickey Waller had gone, and knew about this guy and they wanted the job, basically. That's what surprised me, because I didn't hear about it."

Mitchell got the gig after jamming with Hendrix and Redding for a third time. "I think I actually asked Chas, the manager, 'What's on offer? What's the deal here?' It was like, 'Well, look. We've got nothing, apart from a chance. There's two weeks' work, basically.' And I'd gone, 'Well, okay. I tell you what. I'll give it a crack. I'll have a go for two weeks.' What have you got to lose? You're 19 years old, and in fairness to the music, there was something that I could see was potentially inspiring."

With no record deal and hardly any original material, Chandler began to book gigs around England for the Experience. "We had no songs when we first started," Mitchell says. "So for the first couple of gigs, we were doing stuff like [Wilson Pickett's] 'Midnight Hour,' anything we could think of, quite honestly." The band's first tour was a series of opening slots for French rocker Johnny Halliday, followed by "anything that was offered," including pubs and pool halls. But the word seeped quickly through the underground about the band's wild stage shows and startling techniques, and record company cronies began to poke around backstage.

Chandler knew that the Experience was ripe for the studio. "Bless his heart," Mitchell says, "Chas was hocking every bass he owned in sight just to subsidize the band and recording time." The first song the Experience recorded was "Hey Joe" at De Lane Lea studios. In its day, it was a perfectly adequate facility, but by today's standard it was practically Jurassic. "Over all those years, the technology changed so much," Mitchell says. "When we first started recording from the Hendrix days, we had Chas Chandler working as the producer. Don't forget, the Animals' 'House of the Rising Sun' cost £4 - which is $8.00, whatever it is - to make and was done in 15 minutes, first take. And it sounded good.

"Obviously, we were fortunate enough to be around some pretty competent engineers. There was a certain amount of talent going around, especially in England then. It strikes me, looking back on it, English engineers made the most of the limited capabilities of the technology. They knew the structure of the rooms and they knew what mikes to use and where to record things from. They would make the most of the acoustics with limited equipment. And Hendrix did have a natural capability of working in the studio. To him, that was like his palate of colors. There are some people who feel very comfortable behind the board and know how things work. He was just very natural with the technology that existed. I don't know how much time he'd spent working in studios before."

Chandler kept the trio working at a frantic pace, rushing them from one gig to the next, while squeezing recording dates into the schedule whenever he could. Writing original material on the run, the band would often learn new songs in the studio, practically as they recorded them. "There were no rules on that stuff," Mitchell says. "There are many things that were just done in the studio, created in the studio, written in the studio, played once, and never played again - onstage or anywhere else. That's it. Consequently, you tend to forget all about them."

But Mitchell can't forget the intense level of creativity that buzzed through the room whenever the Experience wrote new material. "I was absolutely free," he says, "but I've never had a fear then or to this day of asking another player, 'What do you hear on this?' If he wanted it to go, 'boom-chicka-chick, boom-chicka-chick,' whatever it might take, 'Tell me what you hear.' Or Jimi would play a basic rhythm and I would see if I could come up with something that would either fit or oppose it.

"I'm just like any other drummer. I stole things from other drummers I could think of. 'Manic Depression' comes to mind. I stole that completely from, of all people, the drummer called Ronnie Stephenson. It came from John Dankworth's 'African Waltz.' It's just what fitted in. I heard this rhythm that Jimi was playing on guitar and I thought, 'Oh yeah, it's that kind of feel.' So thank you Ronny Stephenson."

Though Mitchell generously gives credit where it's due, his humility underplays the deep divide that separated jazz cats from rockers when he recorded "Manic Depression." In a radical moment of inspiration, by adapting Stephenson's jazzy "African Waltz" groove to one of the heaviest rock songs ever written, Mitchell cast aside artificial barriers and foreshadowed the jazz fusion movement that followed in the early '70s. He did this on song after song from Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold As Love, and Electric Ladyland, raising the stakes several notches for every rock drummer who suddenly had to labor over the licks that Mitchell whipped out so effortlessly.

Back then, he wasn't trying to change rock and roll. He just wanted to lay down some great drum tracks. "How the heck do you know?" he asks. "You weren't thinking of putting down something for posterity's sake. It was important to try to put down the best music you could, because there was a very competitive spirit. It was like the be-bop era, it's a very cutting situation, which is very healthy. And of course, in those days, just because it happened to be the '60s, there were a lot of bands from the same area and everyone was trying to outdo each other."

These chops shootouts often happened onstage, during extended jams at after-hours gigs, where musicians would show up to sit in with other bands. Mitchell remembers encouraging drummers like Tony Williams and Buddy Miles to play with the Experience, so that he could hear how the group sounded. And Hendrix would take Mitchell to check out other bands, and the two of them would often sit in.

"After the concert you'd go back to the hotel," Mitchell says, "and it was like, 'Hey, I know this guitarist down the road,' Roy Buchanan or Cornell Dupree, whoever it would be, because he knew these people from being on the road or from the south side of Chicago. I'd go along and was privileged to take those chances to have a play with these people. Jimi would always insist that the two of us would play together, which could be very strange at times.

"I ended up playing one thing in New York with Joe Tex and his big band - and this ain't Count Basie! Jimi woke me up in the hotel in New York and it was about 2 o'clock in the morning, 'Mitch, come on. You've got to come.' 'Huh, what?' I think it was something like a Black Panther reunion or whatever the deal was. I was in the middle of this huge situation in some ballroom, and it was like, 'Shit or get off the pot.' I was very grateful to be around this situation.

"I also got invited up to Miles Davis' house on a Sunday. John McLaughlin had just come in to New York and he was just starting to do some work with Miles with that old Gibson acoustic guitar and Miles at the piano. I was just sitting there taking it in. Suddenly there was this voice like, 'Hey, drummer!' So I looked around. 'Hey drummer! You're a drummer, right?' What was I supposed to say? 'Yes sir, I'm a drummer.' 'Come play.' And there's no drums. So I went to the kitchen and got a couple of pan scrubbers and just made noise. We played for a little bit and, 'Okay, can you be at CBS at 2?' And that was it. I was at CBS at 2 the next day with a brand new Gretsch kit from Tony Williams. And I still have that kit to this day."

Oh, if one could only have been a fly on the wall at that session, or, for that matter, at any session during the late '60s and early '70s where Mitchell played his heart out. Imagine watching him shape ideas emanating from Hendrix's guitar, spontaneously interpreting material that would inspire generations of players to reach a bit further beyond their grasps.

Might as well face facts. The best we can expect is to hear him describe, in his own words, the relationship he shared with his friend and partner, Jimi Hendrix. "There are a lot of things that we never said," Mitchell says. "I think what it comes down to is a kind of mutual respect for each other. Musically, I'd give him a hard time, he'd give me a hard time, though it was a very compatible situation from my side. It was very interesting to work with someone who would give you that ultimate freedom that seemed to have whatever time existed in your head. There were no boundaries, there were no limits at all. Jimi was irreplaceable, both as a friend and a musician. I miss him as much today."

--originally published February, 1998